We humans are terrible with passwords. For that reason alone, developers make remembering and typing passwords a living hell. They want us to expand the character set by adding capital letters, numbers and special characters. And they want us to change our password at certain intervals. After decades of password use, what are the results so far? Do our passwords keep up with the exponential increases in computing power? Let's find out.

Before we start: the numbers used for bruteforce attacks vary because I used different tools. They each consider different pc performance when calculating these estimates. The linked resources provide more technical detail.

It all started with some questions on the usability of password requirements. It's a terrible user experience to come up with a unique password every time. It needs a capital letter, a number, a special character and a lowercase letter. Also, let it be at least 8 characters long, with a maximum of 16. Are you still with me?

Such password requirements are archaic. Technological advances have made it possible to bruteforce shorter passwords in no time. So, is there a better way? We'll get to that. But before we do so, we should dive into the world of password cracking.

How long to crack?

If we take a basic, non-encrypted scenario, passwords are stored as either plain text or as hashes. Hashes are one-way functions that generate a representation of a password. When you run a password through a hashing function, it will always produce the same output. What's so great about hashes is that they're impossible to convert back to plain text.

Your password should always be stored as a hash, which makes it unrecognisable as that specific password. When you enter your password on your next visit, your entry is hashed again and compared to the stored hash. There's more to it, but those are the basics.

How do these passwords get cracked then? Let's take the password cracking1. It gives us the same hash every time. That means that you can enter your password on a website and they know it's correct without knowing your password. At the same time, a bad guy can keep guessing passwords and compare their hashes to your password hash. If he finds the right one, he knows what password you used. If he doesn't try to be smart, but just guess it by performing as many guesses as possible, we call it bruteforcing. It's the most basic technique. A hacker will just try every password until one works.

Cracking a hash is considerably more difficult than simply reading a password from plain text. But it's not that much more difficult when you want to keep your simple password from being guessed. Raw computing power can decipher your password. And the easier your password is, the faster it can be cracked. That's one of the main reasons we see password requirements: to make our passwords stronger.

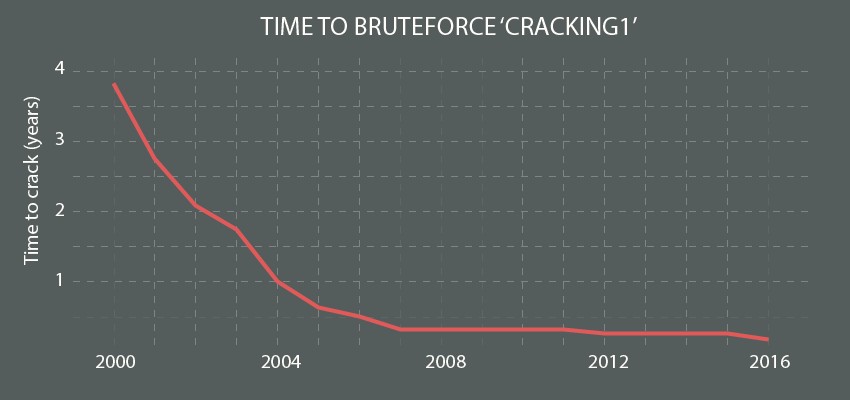

But how long does it take to crack a password? I used data from BetterBuys password checking tool. They assume the use of a reasonably powerful home computer (technical specs: i5 6600K for 2015, CPU only). As the graph illustrates, the time to crack our example of cracking1 was 3 years and 10 months in 2000. In 2016, this was down to 2 months and 4 weeks. That is, if you bruteforce it on your average home computer.

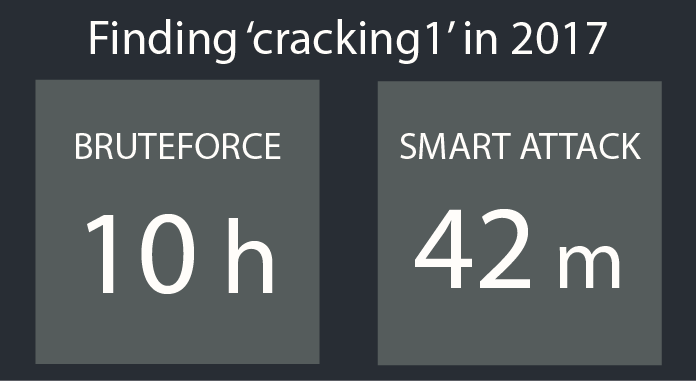

If we can believe a tool to check bruteforce times for 2017 on pumped up computers, we see that cracking1 takes a mere 10 hours to bruteforce. They assume a considerably more powerful set-up. Given the options to rent raw computing power in the Cloud, we can state that bruteforcing is a limit of budget rather than time. The only reason not to crack a password is because it would be too expensive for its reward.

{.imgright}

{.imgright}

In the meantime, hackers have become smarter as well. They created dictionaries to use when cracking passwords. Cracking dictionaries contain both common passwords and English words. cracking1 isn't in such dictionaries because of its number. That's no help though, because cracking is. The most efficient way to crack a password is by trying a dictionary with numbers if it doesn't work without.

This is much faster than bruteforcing. We check our bruteforce case for a better time with the How Secure is My Password tool. We see that it takes a whopping 42 minutes to crack. It even tells us it may be a word and a number. How reassuring.

While basic knowledge of bruteforcing may make you believe that a longer password is better, that may not be the case. One common example going around on the internet is of an xkcd comic on password strength. It suggests using a sentence comprised of four random English words.

And it's true. Sentences with dictionary words are more secure than single-word complex passwords. However, a study from Cambridge University found that they can be guessed with only a little more effort. More secure, but not by a large margin.

With the exponential growth of computing power, the run-of-the-mill passwords have lagged behind. They have not become exponentially more complex, which made them easier to crack. The idea behind password requirements is to make your passwords more complex. But do they achieve their goals?

How password requirements help

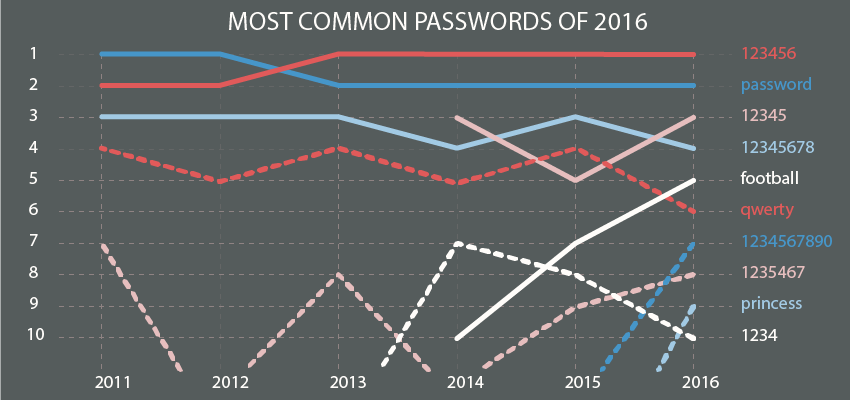

If we look at the population at large, we see that there is a no real development in the most used passwords. They're so easy a toddler could guess them. And so, to make the internet a safer place, administrators and developers are working overtime. At some point, they thought of password requirements.

The question here is: do they help? They're not used much if we consider the most common passwords, but let's put that aside for now. I've checked the password cracking with some of the most-used requirements against a tool with a dictionary:

The password is at least 8 characters.

The password contains lowercase letters. cracking takes 5 seconds.

The password contains uppercase letters. Cracking takes 22 minutes.

The password contains a number. Cr4cking takes 2 hours.

The password contains a special character. Cr4ck!ng takes 9 hours.

Not bad. We went from 5 seconds to 9 hours by changing some of the characters around. But, as stated said before, longer passwords are better. So, let's try another requirement we see quite often.

- The password is at most 16 characters. Let's roll with that and we get: Cr4ck!ngcracking. This would take 1 trillion years to bruteforce.

Wow! By using the maximum password length, we can substantially increase the time it takes to bruteforce a password. I'm impressed. There's only one issue: we're still very vulnerable to dictionary attacks. Cracking is an English word, and so-called leetspeek substitutes such as 4 instead of A and ! instead of I give a false sense of security.

Let's do some math on leetspeek. We can consider substitute vowels as extending our character set by a little. If we only use normal characters, lowercase, we have 28 letters in the alphabet. For 8 characters, that gives us 28^8 options, or 377.8 billion.

When we use the most common leetspeek, we get a character set of 36 options. That's 2.8 trillion possible combinations. Sounds nice, but a single high-performance computer can calculate up to 2 billion possibilities per second. That means our password with 2.8 trillion possibilities is cracked in a maximum of 23.5 minutes when we play smart. For 16 characters, that time grows exponentially. We're not taking into account smarter dictionary attacks here.

Password requirements do help, but they aren't adequate in protecting us from bruteforce attacks. If someone comes with a sledgehammer, a padlock isn't enough. Nowadays, companies such as Twitter, are using alternative ways to help users pick stronger passwords. They do this by disallowing the use of common options. This makes dictionary attacks harder to do, securing us a little bit more.

The issues with password requirements

But this article was about the archaic password rules set up by those requesting them. Why am I against these requirements? Didn't I provide evidence in supporting these requirements? Unfortunately, that's only half the story.

First off, we must recognise that the general user is uninformed about passwords. By reading this article, your understanding of password security is way above average. And we also know that users can't be bothered to inform themselves.

Trusting users to choose and remember a difficult password for yet another service is impossible.

This means that they will choose the easiest password a system will accept. Proof of this is the graph of the most common passwords in 2016. The leading items still are password and 123456. Trusting users to choose and remember a difficult password for yet another service is impossible. If the option exists, they will most often choose password_1234.

Second, passwords get harder to crack the more entropy -- or randomness -- they have. I use LastPass as a password manager, which generates my passwords for me. If I ask it for a random 16-character password right now, I get 677C1$RTRTOPZTlb. No dictionary in the world will help you with that. In fact, this is much safer than our previous attempt at a 16-character password.

One problem with this approach is that you must exclude a lot of possible passwords. They do not meet the minimum requirements. A 16-character password consisting of only lower- and uppercase characters is not good enough. Limiting this randomness makes the number of possible combinations smaller. Protecting users from picking an unsafe 'password' lowers the security of computer-generated passwords. The loss is rather small, but even so it's a loss.

Third on the list is that a lot of password requirements also include updating passwords regularly. This may seem like a good approach to ensure that old stolen passwords are useless. But it also creates a culture where users will use easy to remember passwords because they must change them so often. That's counter-productive to our security goals.

The fourth and final point is that the rules chosen are often incomplete. Some websites make half an attempt, such as asking for at least one number. Others go overboard, asking for 2 numbers, 2 uppercase, 2 lowercase and 2 special characters on a minimum length of 8. And even in that case, the first option is safer than the last. When you think about it, limiting the possibilities makes it easier for our attackers to predict what a password could be.

Password requirements in their current form are user-unfriendly and generator-unfriendly. They take the worst of both worlds by using the current paradigm of passwords difficult for humans. This hinders users in selecting the safest possible passwords, which is against everyone's own best interest. Research and math has shown us that these requirements do little to improve security with the growth of computing power.

Proper password requirements

NIST, the U.S. National Institute for Standards in Technology, published new digital identity guidelines in 2016. One of their recommendations is to not use any composition rules. They advise to make password requirements user friendly by putting the burden of security on the verifier as much as possible.

Their second point is to allow longer maximum passwords, of up to 64 characters. No more limit of 16 characters for users who want to generate their passwords. This goes with the advice that the absolute minimum password length should be 8 characters, with support for longer passwords.

The third is also a wonderful recommendation: no more knowledge-based authentication and hints. NIST has supposedly taken some lessons from the 2013 Adobe security breach. In this breach, both passwords and password hints were retrieved. If you have the hash and 3 security questions, it becomes increasingly easy to guess the password. Some actual examples for users using password were:

The password is password

Password

Rhymes with assword

Thus, I rest my case.

NIST's final recommendation is to allow every Unicode character. This is a character set of 136.755 characters, which includes most of the world writing systems. In this set, you'll find 139 modern and historic scripts, as well as symbols and emojis. Yes, you should be able to use the poop emoji in your passwords according to NIST.

They have more suggestions, but these are all for the application providers. These are checking passwords against dictionaries (you know why that's important) and no password expiration without reason. NIST also provides advice on how to safely store passwords, but that's too technical for this article.

A final word

While these new requirements go a long way in making passwords more user-friendly, we're not quite there yet. Developments such as two-factor authentication are becoming more common as well. They go a long way to ensure that the user attempting to log in is the correct user, but it doesn't protect passwords from being stolen.

Another development is the rise of password managers. These are another great tool to use, as they generate and manage random passwords for you. All you need to do is remember one secure password as your vault key. Just don't put your banking and email passwords in there, you want to be able to access those in case something goes wrong. Check out LastPass and KeePass if you’re interested.